Bruckner’s Sixth is the only work among all his symphonies that does not have the “Bruckner problem” of versions. It was composed during 1879 and 1881, and has never been altered by the composer. It’s probably because Bruckner was in the period of great confidence with his symphonic works.

Bruckner’s Sixth is the only work among all his symphonies that does not have the “Bruckner problem” of versions. It was composed during 1879 and 1881, and has never been altered by the composer. It’s probably because Bruckner was in the period of great confidence with his symphonic works.

The symphony has evidently not been popular and less performed, at least historically. However nowadays the work is getting performed more often, and recordings emerge abundantly. Tovey wrote that “if we clear out minds, not only of prejudice but of wrong points of view, and treat Bruckner’s Sixth Symphony as a kind of music we have never heard before, I have no doubt that its high quality will strike us at every moment”.[1] In my case, it struck me on my first listening.

The Sixth is probably the most unique work among all Bruckner’s symphonies. Its emphasis and masterful use of rhythmic elements is not seen elsewhere. Question is, does this uniqueness come from the “lack of hallmarks” of all the others, as some scholars considered being the reason of the work’s lack of public acceptance, or it’s more from the characteristics that stand out among the rest, as said by Bruckner himself being his boldest? To me it’s certainly the latter. On one hand we can clearly see the Sixth continues to stand firmly on the Brucknarian common ground:

- The overall four-movement structure, with two outer movements and an Adagio and Scherzo in the middle

- The well recognized “Bruckner rhythm” (duplet + triplet); it is not only prominent but a driving force in the first movement

- The typical 3-subject theme layout, with the main subject being motiffic, the 2nd being melodic and the 3rd being rhythmic

On the other hand, Bruckner employed some techniques that are not seen in his other symphonies, before and after the Sixth:

- Unlike the ternary form often seen in the Adagio movements of other works, this Adagio is in sonata form. Simpson stated that “it is one of the largest and most perfectly realized slow sonata designs since the Adagio sostenuto of Beethoven’s Hammerklavier sonata”.[2]

- The 2+3 rhythm is used in the opening, replacing the typical mysterious string tremolo, but more importantly, serves as the ostinato background of the first subject, and permeates the entire first movement

- A poly-rhythmic pattern is used on the 2nd subject of the 1st movement, combining 4/4 melodic line with a double triplet accompaniment on the base, but also shifting emphasis between the two

Movements

I. Majestoso

The movement opens with a rhythmic pattern in pianissimo and high on the strings:

Its structure is very similar to the hallmark “Bruckner rhythm” (i.e. duplet + triplet), and is prominent throughout the first movement, and becomes an underpinning driving force. At the opening, it is an ostinato accompanies the main theme group on the lower strings, with a rather dark tone. The theme group has two parts, here’s the 4-bar Part A:

That subject is echoed by a lone horn. Afterwards the theme moves on to Part B, which is based a motif a bit more energetic:

This motif is important, for both being one of the core rhythmic elements driving the first movement (especially in development), and also providing unity of the whole symphony by foreshadowing the main theme of second movement (which gets further transformed in the finale).

Here, the woodwinds take that dotted rhythm in bar 15, continue on quietly, and soon lead to a powerful restatement the entire main theme group by the full orchestra; with the fortissimo dynamics, the bright brass sound, and the pounding of the timpani on the opening rhythmic device, the sense of Majestoso as the movement titled cannot be further evident. Per Simpson, Bruckner has never done this before at the beginning of a symphony.[2]

| Part A: |

Part B: |

The most notable feature of the second theme group is its complex rhythmic structure. The outer line by violins maintains a rather simple 4/4 meter, but is accompanied by pizzicato of lower strings in a pattern of two quarter note triplets:

Similar to the main theme group, this one also consists of two 4-bar parts:

| Part A: |

Part B: |

As the two parts get restated with some variation, the double triplet pattern gains dominance by bar 61, and then third part emerges on the woodwinds, luminous and refreshing:

Again just like how the main theme group is reintroduced, the second group enters again now with the lower strings starting forte on the triplet rhythms, and the theme presented in a brighter and delightful mood,:

A third theme emerges after short development, emphasized fortississimo by the brass, with a dotted rhythm, repeating 4 bars, bringing a strong contrast to the lyrical second group:

We don’t hear this theme developed as much, but the eighth note triplet rhythmic element becomes obsessively prevalent through the end of exposition, and further into development. It is essentially the core motif that drives the momentum of the whole movement. Here’s an example where the triplets are played by solo flute ending the exposition, and immediately picked up by the strings into development:

And here’s the brilliant use of inversion on the main theme (part A) following above section in development. It’s amazing how Bruckner not only inverted the notes but also completely changed the opening theme’s dark mood into such a beautiful uplifting tune. And, notice the triplet ostinato on the the lower strings:

The above goes on for a long 24-bar stretch, with brass joining in the last 8 bars, then Bruckner uses inversion again on part B of the main theme, starting on the horn:

The movement now comes to the end of development, with both the woodwinds accelerating on the dotted rhythm, same with the triplets on the strings, together building up a climax leading to recapitulation.

The most notable feature of the recapitulation, as many musicologists have written about, is Bruckner’s ingenious handling of both thematic (some referred to as modular) and tonal (or formal) return of the main theme. Per Korstvedt, the reappearance of the primary theme (m. 195) does not coincide with the return of the tonic (m. 209)[3]. That is, the above excerpt, starting at m. 183, begins the buildup that arrives at m. 195, which is considered the thematic return of main theme, not yet on the home key A major:

In only 14 bars after start of the reappearance (actually only 6 bars, taking out the original two 4-bar phrase of the theme), we hear the tonal return of the main theme:

Simpson noted that “Bruckner’s stroke is amazingly abrupt, especially considered in relation to the time-scale of the movement as a whole”[2]. True. It really does not take a pro (as in my case) to feel the magnificent and powerful return to the home of main theme, a sense of leaping into an even higher climax, in that magical two bars as the thunderous roll of the timpani pounding into our ears:

At bar 229, we finally hear the original open theme returning back on the lower strings, with an embellishment by the oboe:

Simpson also noted that the original order of main themes is reversed, i.e. the strong counterstatement comes in first and the soft opening comes second[2]. I guess given that the thematic return at m. 195 is already on a climax, it’s probably only natural the formal return of the main theme (m. 209) would start with the forceful presentation.

Now the second theme group repeated, and as it quiets down with the quarter note triplets stilling lingering, the third theme just burst in without any precursor or transition. Talk about “abruptness” of Bruckner’s “block” style!

As the quaver triplets continue after the third theme and calms down with a diminuendo, Bruckner starts his coda. The beauty and brilliance of this coda simply cannot be understated. Tovey stated that the coda is one of the greatest passages Bruckner ever wrote[1]. It starts by solo oboe singing out a transformed main theme (part A), again through inversion, calm and contemplative, remarkably different from the bright color of the one in development on the high strings:

French horns then join the oboe on the 2nd 4-bar phrase, but gradually gain prominence while oboe fades away; the theme continues to evolve and, more importantly to the effect of this passage, traverse through various keys, with the melody climbing higher on the registry, with the trumpet echoing along the way.

In the middle part of the coda, the horn now narrows down to the quarter note triplets of the main theme, while strings dancing around it with the continuous quaver triplets.

Soon the string takes dominance playing the triplets, and then trumpets blasting stretching long notes, the coda builds up great momentum towards a climax. After a brief 4-bar line humming by the lone horn for the last time, the main theme finally comes back in full force, with the timpani pounding out ostinato rhythm, the Finale is propelled into a glorious conclusion.

II. Adagio: Sehr feierlich (Very solemnly)

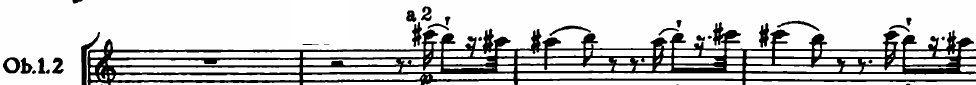

The second movement is an Adagio and in the classic sonata form. It opens its main theme with a solemn tune on the strings, highlighted by a beautiful lament by the solo oboe:

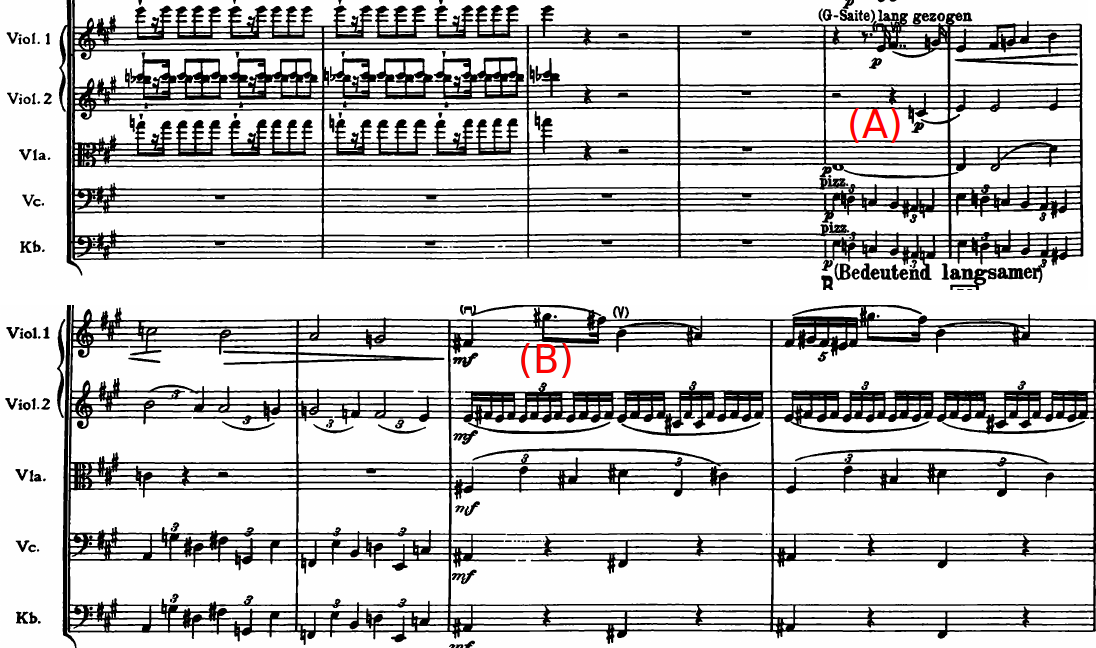

The theme is rich in texture. We hear three elements here. In first 4-bar phrase opens on a steady downward ostinato scale by cello and base (A), along with the broad melody on violins (B); on the repeat the oboe lament (C) arrives.

After a short elaboration, the cantabile second theme is sung by the strings, alternating between cellos and violins:

The theme evolves in similar fashion as the main theme, expanding its core motifs (one quarter + 4 eights) and reaching a climax before it calms down, and then enters the third theme, grim in mood, much like a funeral march (punctuated by the dotted rhythm of the timpani):

Overall the development of this movement is concise, merely 23 bars (m.69-92). It starts by taking first theme’s (A) part to the high woodwinds, then onto the strings, before calming down to a series of recall of the oboe motif (main theme (C)).

When the main theme comes back at the beginning of recapitulation, it’s presented in a new texture. The base ostinato (part A) turns from four quarter notes to a pulsating four quaver triplets, paired with four groups of semiquavers on the violins; the rhythmic change adds agitation to the mood.[1] Oboe lament motif (C) is first repeated, with (B) now on woodwinds, and then horn emerges and takes over the Oboe theme (C):

The reappearance of second theme and the funeral march more or less remain consistent with exposition, but shortened to give room to the coda. In the end we hear a final call of the main theme on the solo oboe. Simpson considered it among Bruckner’s “wisest and tenderest utterances”.[2]

The movement ends quietly on a descending scale recalling the very first bar of the Adagio.

III. Scherzo: Nicht schnell (Not fast) - Trio: Langsam (Slowly)

The scherzo has a typical Bruckner structure, and on the score it is marked “Nicht schnell” (Not Fast); combined with a slow Trio (Langsam), this scherzo movement seems slower than typical.

The main theme is pretty clear on its texture, which consists of three rhythmic patterns woven together: steady beats on the lower strings, accompaniment with quaver triplets on violins, and a brief motif with repetition and descending arpeggio on the woodwinds:

This is far from a normal “theme” but more of a composite rhythmic structure. Wolff noted that the lack of material gives the movement weightless character.[4]

The Trio has a unique texture, the string pizzicato alternates with a grand horn chorale, all rhythmically pronounced on the 2/4 time, and are followed by melodic line on the woodwinds:

How do we describe the mood of this movement? Quoting Simpson again here:

Quiet though much of it is, and delicate, it nevertheless creates a sense of suppressed power…We sense a soft drumming in the earth. A door flies wide with a flare of light and din; there is the smith and the anvil.[2]

Well I thought this passage below from the scherzo, where the opening theme group comes back and leads to its first climax, with a crescendo buildup that leads to a boisterous shoutout on the trumpet, illustrates pretty well the sense of “door flies wide with a flare of light”:

IV. Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell (With motion, but not too fast)

The Finale is another sonata form movement, moderate in size but not as straightforward as typically anticipated. It opens with an introduction on the strings, mood is cloudy filled with uncertainty:

As the phrase repeats, it is punctuated by a series of abrupt brass calls, anticipating the main theme that ensues, so strong and affirmative, completely sweeping away any doubts from the opening bars; the accompaniment by the woodwinds and violins on the high register further intensifies the forward momentum. The theme has two parts, part A starts at bar 32:

Part B immediately follows, at bar 37:

After taking a 2-bar breath, the brass fanfare comes back and climbs up to an even stronger peak (fff at bar 47). Then, with a solo horn hanging on the last breath of the main theme, comes the innocent two-voice second theme on the violins:

The theme develops and becomes more excited, and leads to the third theme, which derives from part B of main theme by doubling the meters (2-bar to 4-bar phrase):

Then, most unexpectedly, we have the oboe lament from the Adagio transformed into a brisk motif on the woodwinds:

Here is the clip of both parts together:

The development is quite extensive, the oboe lament variation theme at one point is inverted:

We hear further variation of the second theme, and finally the brass fanfare starts to come back, eventually reaches back to the opening main theme on the home key, marking the start of recapitulation.

The coda starts with solo oboe recalling part B of the main theme, and then comes the main theme (part A) in full force. Here the opening theme from the first movement is called out on the trombone, mixed with quarter note triplets rhythm of the opening second theme, all combined with the the Finale main theme, reaching the powerful and glorious end:

[1] Tovey, Donald Francis. Essays in Musical Analysis, Vol II. Oxford University Press, 1966. p.79/81/82

[2] Simpson, Robert. The Essence of Bruckner. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1992. p. 157/152/155/156/157/160

[3] Korstvedt, Benjamin M. ‘Harmonic daring’ and symphonic design in the Sixth Symphony: an essay in historical musical analysis. Chapter 7, Perspectives on Anton Bruckner, Routeledge, 2016. p. 191

[4] Wolff, Werner. Anton Brucker: Rustic Genius, E.P. Dutton & Co., 1942. p.223